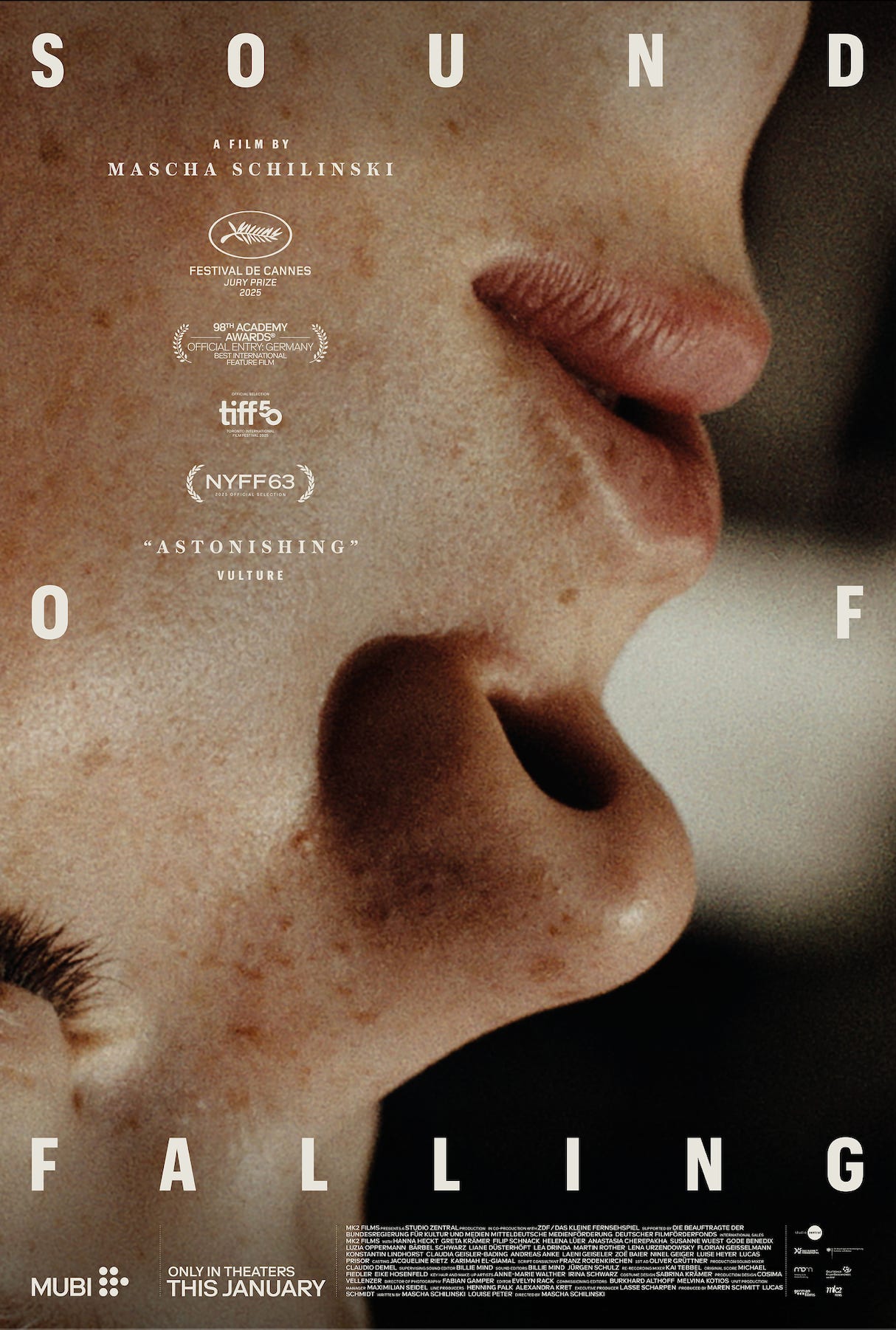

Sound of Falling: "this is the “unpitchable” film, because it’s about memory itself and how eruptive, associative, and non‑linear memory is."

A vHopeful conversation with Mascha Schilinski, Writer, Director of the Oscar-shortlisted feature film from Germany

Four girls, Alma (1910s), Erika (1940s), Angelika (1980s), and Lenka (2020s) each spend their youth on the same farm in northern Germany. As the home evolves over a century, echoes of the past linger in its walls. Though separated by time, their lives begin to mirror each other, revealing shared secrets that have been kept hidden.

the transcript has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Note: the man in the middle of the video is translator, Oliver Latsch. Although I am German Jewish, I have yet to learn more than a few phrases in German, like the new one that Oliver taught me before the conversation with Mascha began: “Everything has an end, only the sausage has two,” which is “Alles hat ein Ende, nur die Wurst hat zwei.” Although watching the film made me want to learn to sing the classic bedtime lullaby, “Wiegenlied: Guten Abend, gut’ Nacht” (often just called Brahms’ Lullaby). It’s a bit hard. Happy to welcome our translator.

Vanessa Hope: Hi, I’m very excited to be joined today by Mascha Schilinski, the director of the Oscar‑shortlisted feature Sound of Falling, which played at the Cannes Film Festival where it won the Jury Prize. She’s coming to us from Berlin, where I understand it’s very cold and she’s just arrived. Maybe, Mascha, tell us how you are, where you are.

Mascha Schilinski: Yes, I just arrived from New York and our heating hasn’t come on yet, so that’s why I’m all packed up. It’s snowy and very, very cold outside.

Vanessa: I’m sorry, that must be slightly painful. We’ll try to make this interview not too painful. I also want to introduce Oliver Latsch, who’s joining us as translator. Thank you for joining. Before we get into the making of Sound of Falling, can you introduce the film in your own words, the way you like to have it introduced?

Mascha: Hi, Oliver—good to see you both. I always say this is the “unpitchable” film, because it’s about memory itself and how eruptive, associative, and non‑linear memory is. It’s about four girls living on the same farm across a century, and we look through their eyes, discovering more and more repressed memories.

Vanessa: The film unfolds with this quiet intensity, and it really does feel like you’re giving us a sense of how memory works. There’s an intimacy between the characters, the setting, and the landscape that feels both external and psychological. It almost feels like you’re inventing a secret language—a new film language—with very strong camera work, sometimes looking through a keyhole, sometimes moving with the characters, combined with incredible sound design. How did you conceive the film’s visual language as a way of expressing emotion or absence, rather than explaining it?

Mascha: I worked with my old friend and co‑writer, Luisa Peter, and during the scriptwriting we realized how interested we were in invisible things—what gets written into our bodies over time, what determines us long before we’re born. We weren’t sure how to turn that into a film, because it all felt more like the territory of a novel.

We collected many small stories about trans‑generational trauma and time, wanting to explore untold, hidden traumas. When we think of trauma, we often think of big events like war, but we wanted to crawl into the pores of the characters and find those tiny secrets no one would ever tell you, even on their deathbed. So it became all about atmosphere—about the secrets that live in our bodies across time for which there are no words. The goal was to create scenes where you can almost hallucinatorily feel that something is hidden and unnameable.

Vanessa: You really achieve that. As you said, the story spans a hundred years, intergenerational trauma, and four generations of female characters. The wars are off‑screen—we never see World War I or II—but so much is conveyed in the performances, which are remarkably restrained and grounded. Some of your key actors are very young; they can’t have had much experience. How did you work with them to build that truth, expressed in their bodies as much as anything else?

Mascha: I love working with children because they have this instinct for the things we’re trying to express. Filmically, I like their perspective: they move through the world like detectives, trying to understand these strange concepts they’re born into without explanation. They can make visible structures and norms that we, as adults, no longer question.

Casting was a huge challenge. With my amazing casting directors, Karima El‑Jimal and Jacqueline Rietz, we looked at hundreds—actually more than a thousand—girls before finding little Alma, played by Hannah. She had done some work before, but not a lead in cinema. I wanted faces you could believe existed in each decade. We ended up with a mix of professional and non‑professional actors, and I wanted to be sure all the kids could access the character but also find their way out again. That exit can be hard, and as directors we sometimes forget how difficult it is to “leave” a role.

With Hannah, I created a simple ritual: every morning I did a “magical shower.” I’d move my hand over her head and say, “Now you’re becoming Alma.” It was incredibly effective—so much so that once, when she went away with her mother for the weekend, I got a call two hours later because she was hysterical that she was still Alma; I had forgotten to “wash” her back into Hannah. They turned around, came back, and when I did the ritual again she said, “Now I’m Hannah. I’m fine, we can go.”

Some of the adult actors were skeptical at first, but after a week they were whispering, “Mascha, can I have the magical shower too?” Sometimes Hannah did it to me, saying, “Now you’re becoming the director.” It sounds playful, but it really helped. And children are so smart; they know immediately when something feels true or false. They have their own ideas about life and death, and I learned a lot from them.

Vanessa: There is a lot about life and death in the film. Without showing war onscreen, so much is lived within the family over generations. The title Sound of Falling is very evocative—both physical and existential. What does it mean to you? What were you thinking when you came up with it?

Mascha: For almost four years we had a working title: The Doctor Says I’ll Be All Right, but I’m Feeling Blue. I loved it, but I was the only one—everyone else thought it was too long. When we were invited into competition at Cannes, we decided we needed another title.

We arrived at Sound of Falling for many reasons. The girls literally fall in the film, but they’re also falling through time and space, and as an audience you’re falling from one time to another too. We wanted a stream of images that could feel like everyone who ever lived in that house might be dreaming or remembering at the same moment. In dreams, we all know the feeling of flying and then falling. I wanted to capture that sensation.

And of course, sound is crucial in the film. We worked with wonderful sound artists—Billy Mind, Jürgen Schulze‑Tabell, Michael Fiedler, Eike Hosenfeld. I already had the “sound of falling” in my head while writing. In the edit, we kept asking: how do we find that sound—a sound that sometimes knows more than the characters, almost like a witness who never forgets, while the characters are trying to repress things in order to survive.

Vanessa: That leads perfectly to my next question. I wondered whether you thought of the house where all the characters live as haunted in some way. Often it feels as if there are ghosts—in fact, the sound and camera together create that feeling. Sometimes we’re observing the characters, sometimes we’re right with them. Were you thinking of it as a haunted house?

Mascha: I was fascinated by the simultaneity of time. We didn’t know how to film all these invisible layers at first. When we found this location, I had the feeling that this house could be the vessel for everything we wanted to explore. It has its own atmosphere: it’s been empty for about fifty years, and when we stayed there one summer, all the furniture was still in place from when the owners left.

You could walk from room to room and see multiple layers of time. We found many old photographs there. The house felt very bright and warm on one hand, and on the other hand very dark and mysterious. That ambiguity—both welcoming and secretive—was perfect for what we were doing.

Vanessa: It definitely feels mysterious, but at the same time incredibly naturalistic and grounded in reality—not at all like a conventional haunted‑house movie. Making any film is hard. In planning and shooting this one, did you encounter any “happy accidents”—instances of chaos or things you couldn’t control that ended up working beautifully in the film?

Mascha: I think there is always some magic on set—hopefully. In this case, there was. It was very challenging to make the film: it’s my first feature after film school, we had a very limited budget, only 33 shooting days, and the children were allowed to work only three hours per day. With one main location, we couldn’t juggle the schedule much.

That created a kind of force. The whole team—every department—was incredibly invested. That’s something you can’t guarantee beforehand. Everyone gave everything to the film in this short time. For me, the “miracle” is that we managed to capture all the images I had in mind without compromising.

Because time was short, I insisted on more than three takes, which made it physically demanding for everyone. With the kids, it was less about rehearsing and more about generating fresh impulses and staying extremely focused to catch a single, fleeting moment that might only happen once. I’m very grateful we were able to do that.

Vanessa: Another miracle you pull off as a director is translating that sense of memory—how it works, how it lives in the body and across generations—into the filmmaking and editing. You capture that on screen. While the house is central, you also have fields and the river; memories move through this elliptical narrative. How did you achieve that?

Mascha: The most important part of this project was the writing. It took us three and a half years. We couldn’t find references for what we wanted to do, and whenever we tried to impose a conventional plot or “proper” character arcs, the script pushed back. It felt like the screenplay was saying: “Don’t do this to me.” The invisible things we cared about disappeared the moment we tried to force structure.

Eventually we understood that we just had to allow images to rise and write them down. We ended up in a kind of hallucinatory process of imagining, then later treating it like a puzzle—searching for connections that were already there. We looked for physical transitions, tactile moments, echoes through time, plantings and payoffs.

In the edit, it became about placement: does a repetition come right after a scene, or half an hour later? How long do we stay with one character before we jump to another decade? At some point we had an initial breakthrough: we threw all the rules out the window. It wasn’t “kill your darlings” as we were taught—on this film it was “embrace your darlings” and make sure they all find a place.

Vanessa: It does have that hallucinatory feeling with echoes and murmurs traveling between generations and characters. At the same time, it feels very photographic—there are photographs in the story, and some frames look like composed photographs themselves. What were your visual influences?

Mascha: Photographs were a huge reference. We used photos we found in the house; there’s one snapshot from the early 1920s of three maids looking directly into the camera. That breaking of the fourth wall became a major inspiration: the idea that the characters might look back at us.

My amazing DOP, Fabian Gamper, and I were also very influenced by the photographer Francesca Woodman. She often works with a ghostly feeling, as if anticipating her own death in her images. That was very inspiring and became a great communication tool across departments.

The script itself reads almost like a novel: every image is on the page, and people could feel what it was about while reading. The directing process was a bit different from more dialogue‑driven films. In the edit, I realized how often I’d spoken directly to the actors during takes because there’s so little dialogue. Sometimes, when I was watching and thinking, “Now turn your head,” I’d suddenly hear my own voice from the shoot saying, “Now turn your head.” It was like talking to myself through time.

Vanessa: That’s really interesting. My last question was going to be about sound design, but you’ve already spoken beautifully about that, unless there’s anything you’d like to add—or about working with your cinematographer, who I understand is also your partner. I’m also curious if becoming a mother yourself, or anticipating that, was in your mind while thinking about generations and systems—both family systems and the broader political systems we’re born into. Ted and I talk about that a lot, and we felt your film conveys it very deeply. As a final thought, is there anything you’d like to add on those fronts?

Mascha: Thank you. I’d love to say more about working with Fabian, because that collaboration is very special. As life partners, he’s there from the very first idea, so he can immediately jump in and think through how to translate these inner images technically—how to find a visual language for them.

For example, we started by testing motion blur inspired by Francesca Woodman, but on screen it looked like a cheesy music‑video effect. So Fabian brought all his knowledge to the table and we ended up working with a simple pinhole lens to create the feeling that certain memories can’t quite be reached anymore. There’s a scene where Alma tries to remember the face of her beloved grandmother who has died, and she can only see fragments, details. There’s a melancholy to that partial remembering. Capturing that through the lens was crucial.

Fabian’s camera became almost a main character—a ghost with a curious gaze, traveling through time and space between all these different girls. Sometimes it feels like one of the characters looking back millions of years later, trying to grasp that they were once alive; sometimes it feels like the universe itself watching them. He also operated and did the Steadicam work.

We couldn’t afford to shoot on film, so he created the film’s grainy, wavy, dreamlike look digitally. We decided not to give each time period a different look because we wanted a single stream of consciousness—or maybe unconsciousness—running through the whole film.

Vanessa: You achieve something extraordinary with the marriage of your writing and direction and his cinematography. Ted and I watch so many films, and I’ve never seen cinematography like this. It’s a must‑see—so evocative and so alive, with the camera playing all these different roles.

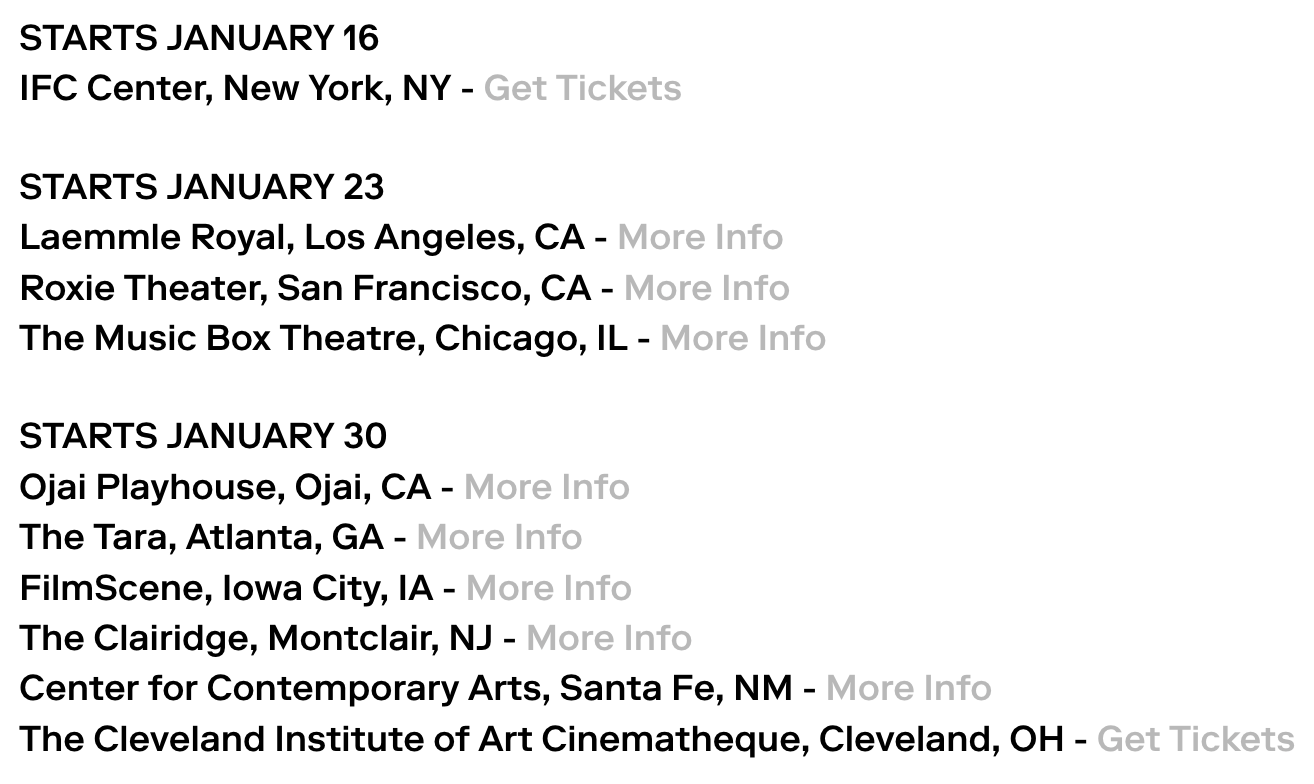

Thank you so much for giving us your time on a busy schedule—and with no heating in freezing Berlin. I’m so sorry; I hope that gets fixed quickly. Good luck at the European Film Awards. Lastly, we should tell people where they can see your film—it’s going to be on MUBI, and there’s a U.S. theatrical release on the 16th, with other European releases to follow.

Mascha: Thank you so much for your time and your questions, Vanessa. Thank you for having me.

Vanessa: We’re getting out ahead and telling everyone to put it in their calendars and make sure they go see your film soon. Thank you again, and thank you, Oliver, for joining us and translating.

Oliver: My pleasure.

Mascha Schilinski is a writer and director born in Berlin. She completed the “Drehbuch- Masterclass” at the Filmschule Hamburg and worked as a writer. Schilinski then began her film directing studies at the Film Academy Baden-Württemberg. Her award-winning medium- length film The Cat was made in her second year of study. In her third year of study, she directed her feature film Dark Blue Girl. The film premiered at the Berlinale 2017 and was nominated for the GWFF Award - Best First Feature. Dark Blue Girl screened at more than forty festivals worldwide and won several international awards. In 2023, she and her co-writer Louise Peter won the Thomas Strittmatter Award for their screenplay Sound of Falling. Sound of Falling won the Jury Prize in the main competition lineup of the 78th Cannes International Film Festival.

Ticket info here: https://mubi.com/en/soundoffalling

And if you need any further enticement…

cannes film festival

winner – jury prize (tie)

european film awards

nominee – best european film

nominee – best european director – mascha schilinski

nominee – best european screenwriter – mascha schilinski, louise peter

nominee – best european casting director – karimah el-giamal, jacqueline rietz

nominee – best european cinematographer – fabian gamper

nominee – best european composer – michael fiedler, eike hosenfeld

nominee – best european costume designer – sabrina krämer

nominee – best european make-up & hair artist – irina schwarz, anne-marie walther

camerimage

winner – silver frog – fabian gamper

chicago international film festival

winner – best director – mascha schilinski

winner – best sound – claudio demel

the gotham awards

nominee – best international feature

nominee – best original screenplay – louise peter, mascha schilinski

british independent film awards

nominee – best international independent film

new york film critics online

nominee – best international feature

london film critics circle

nominee – technical achievement award – sabrina krämer

motion picture sound editors golden reel awards

nominee – outstanding achievement in sound editing (feature, international)

This was a major arthouse hit in Germany where, interestingly, the title is „In die Sonne schauen“ - or „Looking into the Sun“.

(It’s often the case that titles of international pictures are changed, sometimes completely, for the German-speaking market.)

Love love love love! Easily my favorite film from last year. Thank you so much Vanessa for bringing this interview to life ❤️