Belén:"The movement that freed Belén was collective, just as film is collective. The problem is when powerful people move forward without considering anyone else, when human lives are worth less...

than oil." A vHopeful Conversation with the Oscar-shortlisted film's Writer, Director, Actress Dolores Fonzi

International Feature Film Shortlist (Argentina) – Academy Awards

Best Foreign Language Film – Critics Choice Awards (Nominee)

Best International Feature – HCA Astra Film Awards (Nominee)

International Film Award (Dolores Fonzi) - CCA Celebration of Latino Cinema & TV

Best Latin American Film - Forqué Awards (Winner)

Audience Award - Biarritz Latin American Festival

Audience Award - Miami Film Festival (GEMS)

Best Supporting Performance, Silver Shell Award (Camila Plaate) - San Sebastian International Film Festival

RVTE Another Look Award, Special Mention (Dolores Fonzi) - San Sebastian International Film Festival

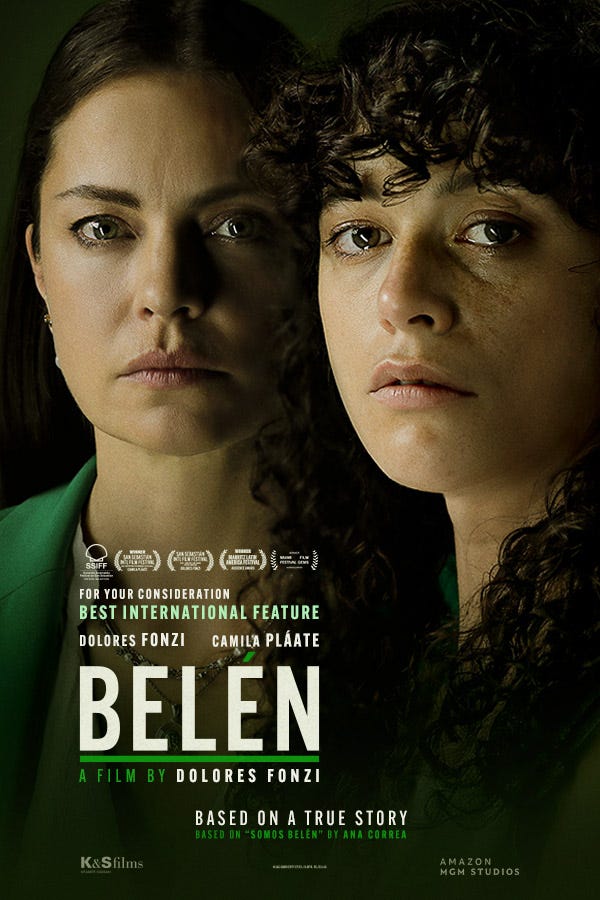

Set in Argentina’s province of Tucumán, BELÉN tells the true story of Julieta (Camila Pláate), a young woman accused of infanticide, and Soledad Deza (Dolores Fonzi), the bold lawyer who risks everything to take on the highly controversial, precedent-setting case. As the trial unfolds, Julieta’s plight becomes a flashpoint in the battle against a conservative legal system – sparking a groundswell of outrage and a growing wave of solidarity that transcends borders.

The transcript has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Note: When editing the video of my conversation with Dolores Fonzi because we spoke much longer than the usual thirty minutes, I cut my intro where I said:

I’m thrilled to be joined today by the writer, director, actress, and star of a profoundly moving and important film, Belén, from Argentina. She’s joining us from the Palm Springs Film Festival. Her film has been gathering awards across the circuit. It’s so exciting to have her here. Thank you for joining us, Dolores.

Dolores Fonzi: Thank you, Vanessa. Thank you for inviting me.

Vanessa: Belén is based on the true story of a young woman in Tucumán, Argentina, who went to a public hospital in pain, unaware she was pregnant, and was then charged with homicide after a fetus was found in a nearby bathroom. What was your first encounter with this story, and what made you want to live with it long enough to make a film—rather than simply follow it as a citizen or activist?

Dolores: I first heard about the case in 2016. I learned that Belén had been imprisoned in Tucumán because of a terrible injustice. Her real lawyer, Soledad Deza, was working to make the case known throughout Argentina, and as an activist, I got involved in meetings about how to help.

Then I was nominated for—and won—an acting award. At the ceremony, I held a sign that said “Freedom for Belén.” People there, including producer Leticia Cristi from K&S Productions, were asking, “Who is Belén?” That gesture drew international press attention to the case and put a spotlight on what was happening in Tucumán.

Two years later, Ana Correa’s book Somos Belén was released, and I went to the launch because I appear in a chapter about actresses who supported the case. Leticia bought the rights to develop a film. At that time I wasn’t yet set to direct, and they initially wanted me just to play Soledad as an actress. Then I directed my first film, Blondi, which I wrote, directed, and acted in. Leticia saw it at a festival and said, “You should do all three here too.”

By the end of 2023, I said yes immediately. The case felt very familiar to me; I knew what it was like to be in the streets fighting for rights. Argentina passed the abortion law in 2020 after a huge movement that began around 2015 with Ni Una Menos and grew with Belén’s case, which helped center reproductive rights in our public debate. I rewrote the script at the beginning of 2024, we shot soon after, and less than a year later, here we are.

Vanessa: It’s incredible—your second feature as a director and already Oscar-shortlisted for Argentina. Congratulations, truly.

Dolores: Thank you. It’s amazing.

Vanessa: In reality, Belén is a pseudonym, and in the film you don’t turn her into a recognizable celebrity victim. Instead, she’s a young woman whose life could stand in for many women’s lives in Argentina or anywhere—including here in the U.S. How did you think about the ethics of fictionalizing her and changing her name while staying faithful to the core of the story and the case?

Dolores: In real life, Belén wanted to stay completely anonymous. She still lives in anonymity, and it was her condition that I not speak publicly about her private life, her specific family, or personal details. I completely understood why.

That condition actually became something powerful for the film. Victims like her are many, but lawyers like Soledad are rare. So rather than particularize one victim, I chose to make her more universal, and to focus in detail on the lawyer, because we need to highlight people like her. That guided my rewrite: putting the emphasis on the lawyer’s private life, how the case affects her, and how she manages helping someone else under pressure.

Belén is also the real pseudonym that the lawyer gave her, and we play with that in the film—Belén meaning Bethlehem, where Jesus was born—and there’s a bit of humor around that given the religious context. So honoring her condition actually helped shape the film in a good way and gave me a clear path through the real case.

Vanessa: It works so beautifully, and the way you direct that relationship is incredibly moving. The actress playing Belén, the physical experience at the beginning of the film, the hopelessness of her situation, and then the way your character as her lawyer brings her into a community—it’s all so powerful.

Your own character, as you said, is not Belén but her lawyer, and a good one, after the first lawyer fails her. Friends had suggested you should play the lawyer. Was it good for you—and challenging—for you to direct yourself in this role? How did you approach it? Your character has such rich detail, and her life feels relatable and real, like she could be any of us.

Dolores: The film has many layers, and for my character it was essential to show the humanity of everyone involved. As an actress, to act truthfully, I need that real sense of being human and close to the audience.

Spending time with the real Soledad Deza was fundamental. We spent a lot of time together, and she was incredibly generous and collaborative. We became friends—she’s actually my lawyer now. Having the real person by your side, trusting you, giving you energy and details, is a gift for an actor. The character’s truthfulness comes largely from her.

At the same time, like in my first film, I wanted to show the daily reality of a woman—with work, motherhood, partnership, and multiple responsibilities. Women often have this multitasking ability, and I wanted to portray that honestly and sometimes humorously, as a kind of relief in the film. We see a woman who is a lawyer, a worker, a mother, a wife, managing real life plus the weight of this case, the pressure of getting this girl released, and the emotional toll it takes.

One key scene for me is when Soledad visits Belén in jail, deeply anguished, and Belén tells her, “I know you’re going to get me out.” That’s the turning point, when we start to believe it might be possible, even as we see Soledad suffering, having nightmares about her responsibility. That combination of intimate struggle and hope is what I want to show in all my films.

Vanessa: You articulated that so well. I love that scene, and so many others: her scenes with her husband, who stands by her even when they’re at risk; the solidarity of her women friends and co-workers. It’s wonderful. I hope everyone sees this film—it’s so important.

As a director, how did you work with your cinematographer and production designer to create such an authentic, lived-in world? Were there films that inspired you?

Dolores: I worked with the same crew from my first film. The cinematographer is Javier Juliá—he’s amazing, one of the best in Argentina. I had the honor of working with him on Blondi and he also shot a film my boyfriend made that was nominated a couple years ago.

For costumes, we essentially copied the real Soledad—her style of clothing, her glasses, her long hair. That long hair was tough in summer; I was suffocating sometimes! But it was important for the character. In Argentina we have a strong film culture, and I’ve been working in film, TV, and theater for about 30 years, so I know many people and feel supported by a great crew.

When you’re an actor directing, you need people you can completely trust. I like to work in an atmosphere of love, respect, and joy, where everyone feels they can propose ideas and where I can delegate. When people feel trusted, they give more, and that exchange is essential. For me, filmmaking is a complex exercise in communication—with a lot of love.

On top of that, I’m a mother of two. I’m here with you today, and it’s my older son’s 17th birthday. He’s in New York with his father and he’s happy, but of course I cried in the morning. That’s life—juggling everything at once. So having a solid, happy crew is crucial.

Vanessa: Happy birthday to him! And you succeed so well with this film. I love that your philosophy is to create an environment of love and trust. You don’t have to be a tyrant or a dictator to be a director.

Dolores: No—and if I were, I don’t think the film would be as good. The audience feels the energy behind a film, and I want that energy to be generous. I want to create, on set, the world I’d like to see outside it.

What would happen if women were the ones managing power in the world?

Vanessa: I’m voting for you already. You direct with tremendous emotional power. The opening sequence is one of the most shocking: Belén in the hospital, vulnerable, in severe physical pain, and then the police burst in. It’s devastating—and it’s happening in America right now too.

How did you figure out how to stage and shoot that opening sequence?

Dolores: I love films that immediately immerse you in their universe. Long takes at the beginning of a film—like in Boogie Nights—are amazing to me. I watch a lot of movies; they’re the material that shapes a director’s voice.

For the opening, that long take felt like the clearest way to show the case: a single blow to the audience. Then they can breathe. The risk was people thinking, “If the whole movie is like this, I’ll die,” but it isn’t. Still, I wanted to put the entire core of the case upfront.

That scene was very hard to do. I wasn’t acting in it; I was only directing. When I’m in a scene as an actress, I’m exposed together with the other actors, building the moment alongside them. Here, I was outside, looking in. It felt like leaving the actress alone in a very vulnerable place.

The whole crew was deeply affected. Some people left the set in tears, others hugged each other. When I went to talk to Camila, who plays Belén, she’d been in that position all day, legs up, shouting and crying through multiple takes. She’s a smoker, so I asked, “Do you want a cigarette?” We were in a closed room; she was desperate. I tried to give her direction and started crying myself, and she said, “Don’t do that!” We were all very sensitive.

We shot that long take over three days. Initially, I wanted it without cuts, but later I allowed myself to cut—it’s important not to be dogmatic. The atmosphere was very heavy, but Camila is incredibly intuitive. You give her a direction, and she just finds a way to do it.

I also wanted to shoot from behind her, so you never fully see her face at first. Anyone can be in her place—that was the idea.

Vanessa: You achieve such a deep emotional connection with the audience. We feel her physical pain, and then the absolute injustice of the police storming into a hospital. It’s instantly clear how wrong it is.

As a director, you also handle three different “worlds” so well: the public hospital, the legal sphere, and the demonstrations in the streets with the green handkerchiefs—such an uplifting and inspiring part of the film. The film is epic in scope yet intimate with its characters. How did you think about framing and sound to balance that?

Dolores: I was very focused on the film’s epic dimension. I knew it needed that. Of course, we had to be precise and respectful with the details of the real case, but the challenge was to translate it cinematically.

For the prison, I wanted a static, almost lifeless camera—a claustrophobic, sterile feeling, especially in scenes like the birthday in jail, where time just passes in this terrible way. Inside, the camera is “dead.” Outside, in the women’s movement, everything is colorful and alive, and the camera moves, follows people, breathes.

We also recreated footage that looks like archival protest material. It’s not real archive; we shot it, but we studied real images from the movement and modeled ours on them. It was important to see Belén’s sister and mother in those marches, witnessing a mobilization happening for their daughter and sister.

The film is a tribute to the women’s movement and to that moment when we felt we could transform society—and did, by winning the abortion law. Even though Soledad is still handling cases like Belén’s today in Tucumán, and similar injustices are happening in the U.S. and around the world, remembering that victory is important. It shows us that if we did it once, we can do it again.

Vanessa: It’s deeply meaningful and needs to be seen globally. And honestly, we need many more films from you.

Another powerful aspect of the film is that Belén’s story isn’t just about gender; it’s also about class and geography—who can speak up and who can’t, who understands the system and who is crushed by it. That’s true in America and worldwide. How did you think about that in the details of the film?

Dolores: For me, a perfect world would be one where a film like this, about women, isn’t labeled just “about gender.” It’s about injustice and about poor people without resources confronting those who have them, and how unbalanced the world is.

In Argentina, some people have asked if I “need” feminine content in my films. I say no—it’s human content. It’s a humanist film. If the word “feminist” bothers them, they should remember that feminism is a form of humanism. The story could be told with male characters and it would still be the same story: a broken system, people judging others to preserve their own power, an illusion of individuality when we actually need collective action.

The movement that freed Belén was collective, just as film is collective. The problem is when powerful people move forward without considering anyone else, when human lives are worth less than something like oil. It’s madness. For years I couldn’t believe Argentina didn’t have an abortion law; people reacted as if just saying the word “abortion” was shocking. But really, it was a question of whether people with resources could safely make decisions while poor women died.

Note: again, for brevity in the video, I cut some of the dialogue you’ll read below from our original extra lengthy conversation.

Vanessa: Exactly. Like you, I’m a cinephile—I watch everything. And I’m so happy you’re Oscar-shortlisted, especially since most of your competition is male directors.

What’s so powerful about your work is that the violence and injustice in your film are lived and experienced; they’re not abstract or stylized. Too often, male directors play with violence for shock or entertainment. For women, this is not a game; it’s oppressive and real.

Dolores: Yes. Men often have the privilege of treating violence as a genre element, something to play with, without needing to change anything. Why would someone with privilege voluntarily give it up? They should, if they’re intelligent and empathetic, but many don’t.

Vanessa: This isn’t a niche issue. What happens to women and how they’re treated is at the core of all violence and inequality.

Dolores: You can’t build a happy society if half the population thinks the other half should go to prison for an obstetric emergency.

Vanessa: Exactly. We’re not less than human.To me, men can help by supporting you, by supporting women directors who are telling these stories and who need opportunities. You should have so many new opportunities now.

Dolores: I hope so. But even before that, if women support each other and make a kind of collective stand—saying, “This film is important, watch it”—we can already change a lot.

Vanessa: I agree! Belén is available on Amazon, and we hope everyone watches it, whether they vote or not. Is there anything else you’d like to add?

Dolores: No, I think this was amazing, Vanessa. I really enjoyed it. Thank you.

Vanessa: Thank you so much for inspiring people around the world with this movie—for making it, and for what you’ve achieved. You’re in the “boys’ club” now, among some of the best films in the race, and you absolutely deserve to be there. I hope you go all the way.

Dolores: Thank you very much.

Dolores Fonzi is an Argentine actress, screenwriter, and director. Throughout her career, she has worked with acclaimed filmmakers such as Damián Szifrón, Fabián Bielinsky, Lucrecia Martel, Santiago Mitre, and Valerio Mastandrea, among others. In 2023, she premiered Blondi, her debut feature as both writer and director, in which she also starred. Belén marks her second film as a writer-director and once again as its lead actress.