"Art, to me, is a commitment—a matter of prioritization. Being an artist is a way of life, not the reverse." -- Ilker Catak

5 Questions #17 : The director of the Oscar nominated "The Teachers' Lounge"

Okay this time round, 5 Questions has become 8. If someone wants to answer more than five, who am I to object?! And Ilker did, so here you go.

Please make sure you see his new feature The Teachers’ Lounge. It accomplishes something remarkable — many things actually — that helped remind me why I am so in awe of cinema. There is something about experiencing a film that delivers truth — and you can only know that when you feel it and see it — that takes the everyday, delivers a sense of life as we know it to be, and transforms into something far larger, rippling out in all directions. That which is small and precise becomes epic and profound. The Teachers’ Lounge does this and more, reminding me again how much I would prefer these “small” movies with giant hearts, minds, and souls than the bloated but empty spectacles the Studios have long put out and now the Global Platforms are parroting.

Granted I may see metaphors for filmmaking in virtually everything, but I certainly saw it in your film, in the teaching, in how we have to learn to balance in shifting sands. We are always learning and always having to bend with the situation and with what the different participants have to offer. How much did you feel that while you were making the film? How apt is the metaphor? What does it get right and what does it miss?

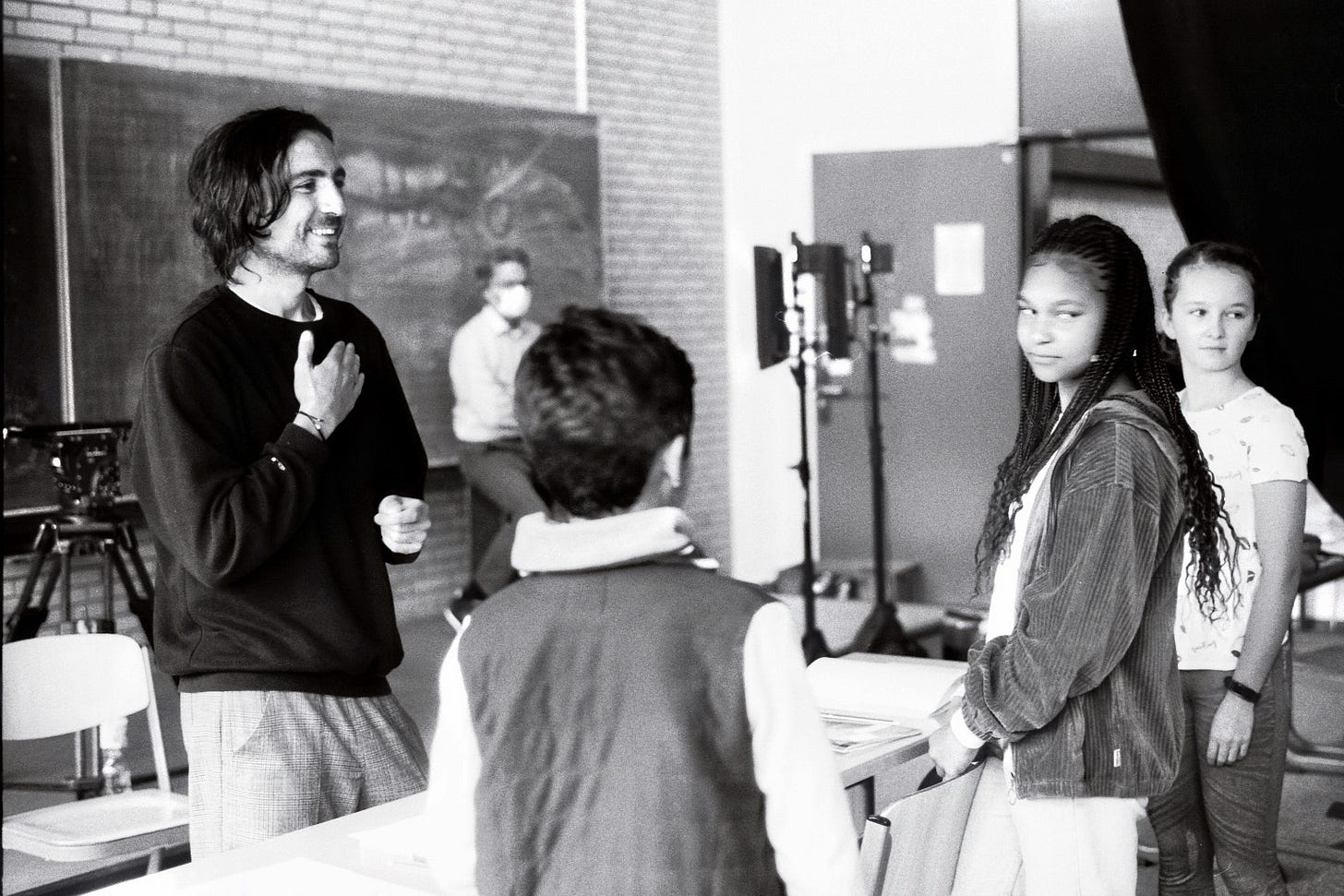

Teaching 7th graders and filmmaking share more similarities than one might initially imagine. Navigating unforeseen situations demands both inner flexibility and a composed demeanor. There are moments when you must swiftly switch gears, asserting, "Alright, let's go; I need everyone to engage now!" Surprisingly, this comparison didn't occur to me during our filming process. However, I did recognize my natural affinity for working with children, leading me to consider my potential as a capable teacher.

Standing before a class and guiding students to extract their best performance mirrors, in some ways, the dynamics of leading a team as a director, yes.

Because the subject required so many children in the film, I suspect you had to work with many non-professionals, and then you had to mix them with professional actors. Can you tell us about the process, and how you dealt with the differences in experiences and methods, and what you did to make it feel so cohesive and of the same world?

Collaborating with non-professionals is consistently enjoyable due to the inherent unpredictability. As Robert Bresson once expressed, the role of a non-professional actor should resonate closely with their own life. In the context of "The Teacher's Lounge," all the kids essentially portrayed what they experience in their daily lives: being students. I believe this authenticity greatly contributed to the genuine look and feel of the project.

One of my favorite themes to explore -- and not just in cinema -- is "Us in the system, and the system in us". Your film captures that beautifully and subtly. How much of this was what you set out to achieve, and where did it naturally evolve? Were you caught by surprise ever? Did you find new ways to bring it out in the edit room?

It wasn't "us in the system, and the system in us," but rather "the road to hell is paved with good intentions." I appreciated the concept that someone can have good intentions yet still make misguided choices, especially within a system that discourages going beyond the expected. The overarching theme of "the individual caught in a system" was present, but when I engage with specific material, these meta questions become secondary. My primary focus is on developing a compelling plot, a dynamic setting, and a moral dilemma that I can immerse my characters in. Once a potent moral dilemma is identified, which is always my primary goal, the question of system versus individual naturally surfaces.

Every film has barriers and obstacles to getting made, but they often are quite distinct too. What were some of the unique challenges you found in the financing, making, and/or release of Teacher's Lounge, and what did you do to overcome them?

I had to defend the notion that this film was crafted for the cinema experience. Financiers were suggesting a television format, proposing a different ending and criticizing the lack of production value, deeming it as mere talking heads. To counter this, I had to articulate why the essence of this film belonged to the cinematic realm rather than television. Inquiries among different individuals revealed the diverse perceptions people have about the movie-going experience. My father, for instance, enjoys spectacles like Avatar, a taste that doesn't align with mine. It's not solely romantic comedies either, which my mother enjoys alongside a large bag of popcorn.

After extensive contemplation and discussions with friends and colleagues, I jotted down my personal definition of cinema. From a spectator's viewpoint, cinema is a space that allows me the freedom to form my own opinions. I relish going to the movies to be stirred, unsettled, and even irritated. I appreciate not fully comprehending a piece of art, because it sticks with me longer. The subsequent discussions and interactions with others, as well as the filmmaker's avant-garde approach when ahead of their time, contribute to the unique cinematic experience.

From a creator's perspective, cinema represents a distinct process of crafting something that isn't merely a product tailored for a specific audience but a quest. It's a personal exploration, an attempt to perceive the world differently. It's also a search within the filmmaking process, arriving on set without a concrete vision for a scene but having confidence that, with sensitivity, awareness, and focus, something beautiful will transpire. This approach, of course, requires time—more shooting days and extended periods for contemplation, which working for the big screen usually provides more likely than a TV production.

When I consider embarking on getting a film made, one of my first questions is “Why this film now?”. So: why this film now?

"Why this film now?" is indeed a pertinent question. I do contemplate it, but the truth is, there is only one story—the best story I have in my arsenal. If I happen to have the luxury of multiple stories at my disposal, a form of "project Darwinism" comes into play. When we pitched "The Teacher's Lounge" to our commissioning editor, there were two other stories in the mix, all at a similar stage but with entirely different themes. She chose the teacher's story, and we agreed, saying, "If this is the one you believe can secure financing, then I will concentrate on it." I find it crucial to have several projects in the pipeline to alleviate the pressure on each one and to involve others in the decision-making process. That said, I recognized that films centered on teachers and students tend to possess a timeless quality. Therefore, the question of "why now" is not solely about the current moment or societal trends...

Hollywood is often called The Dream Factory, and to that end I often feel it has historically served up idealized versions of our characters and most professions. I don't know about you but I never got the teacher who changed my life. I found it quite wonderful instead to find a teacher in your film, that actually reminded me of many I know (it was and still is my family's core profession) where things go wrong despite all the efforts to the contrary. Is your film a rebellion against that sort of Hollywoodization of labor? Did you set out determined to "tell it like it is"? Did you have a way to measure truth? Accuracy? Authenticity? Because it certainly feels like you achieved it!

We didn't think about Hollywood when we created CARLA NOWAK. At least I didn't... But I knew that we wanted to create a character with flaws, stubbornness, and an unwavering spirit. The film was meant to be a pressure cooker, and one of the rules in the writing process was to say: if there is no conflict in a scene, we probably don't need it. Ambiguity was crucial. Johannes, my co-writer, and I are drawn to characters that you cannot spot as solely good or bad.

Regarding the rebellion against the Hollywoodization of work, I can say that we focused more on the authentic portrayal of conflicts and human weaknesses, rather than adhering to an idealized version. The intention was to depict the reality and complexity of human life without succumbing to the usual clichés.

The measurement of truth, accuracy, and authenticity in our film relied heavily on the honesty and depth of the human experiences we wanted to portray. Overall, our goal was to explore the complexity of life in a way that goes beyond stereotypical representations.

What does it mean to you to be disciplined in your work and how do you achieve it? How does it help? Where does it create challenges?

It seems like maintaining discipline has become a more demanding task than it used to be. One contributing factor is the increased number of people seeking my attention—too many phone calls, too many emails. To preserve my discipline, I must master the skill of prioritization. My daily routines, including workouts, dietary habits, and ensuring adequate sleep, have taken on heightened importance and now top the list of priorities. Beyond that, there are people and projects to consider. At times, I find myself overwhelmed, driven by the desire to tackle everything simultaneously, and I struggle to say NO. Eventually, I wake up to the realization that I'm feeling burnt out. I recently learned that Christopher Nolan doesn't use a cell phone. I completely understand why.

What are your recommendations for growing as a director? And how does it align with the demands of earning a living and having a life? Do you try to mix in commercial work or is it best to avoid? How do you improve your craft when you don’t have a pile of gold under your bed?

It is crucial for me to tread new territories with each film I undertake. Avoiding repetition is paramount, as I believe true growth as a director comes from exploring diverse themes and genres. When it comes to earnings, I often reflect on the words of John Cassavetes. He emphasized that to be an artist, one must set aside existential concerns. There were periods in my life when I earned very little, leading a more modest existence. Art, to me, is a commitment—a matter of prioritization. Being an artist is a way of life, not the reverse. I genuinely believe that if one remains dedicated to their art and wholeheartedly believes in it, financial rewards will eventually follow.

Ilker Çatak is a German-Turkish director and screenwriter from Berlin. He grew up in Berlin and Istanbul, and before studying film, he worked for four years on German and international film productions. He has directed over a dozen short films, and his graduation film "Sadakat" won the Student Academy Award in Gold in 2015. His fourth feature film, "Das Lehrerzimmer" (The Teacher's Lounge), is Germany's submission for the Best International Film category at the 2024 Oscars. The film premiered in the Panorama section of the Berlinale in 2023 and received multiple awards, including five German Film Awards. Çatak has also received numerous awards for his other short and feature films, such as "Es gilt das gesprochene Wort" (I was, I am, I will be).

Thank you for giving me another title to put on my watch list. It seems that all of the individuals you have questioned about their films are already recognized as artists by other filmmakers and festivals around the world. I am more interested in those that are making extremely important films that could change the world. Maybe they are not artists of the caliber of those you are interviewing, but they are very deserving of having their films seen by a worldwide audience.