"Behind all the numbers and statistics are people with dreams, and families. We want to humanize this number." -- Matteo Garrone

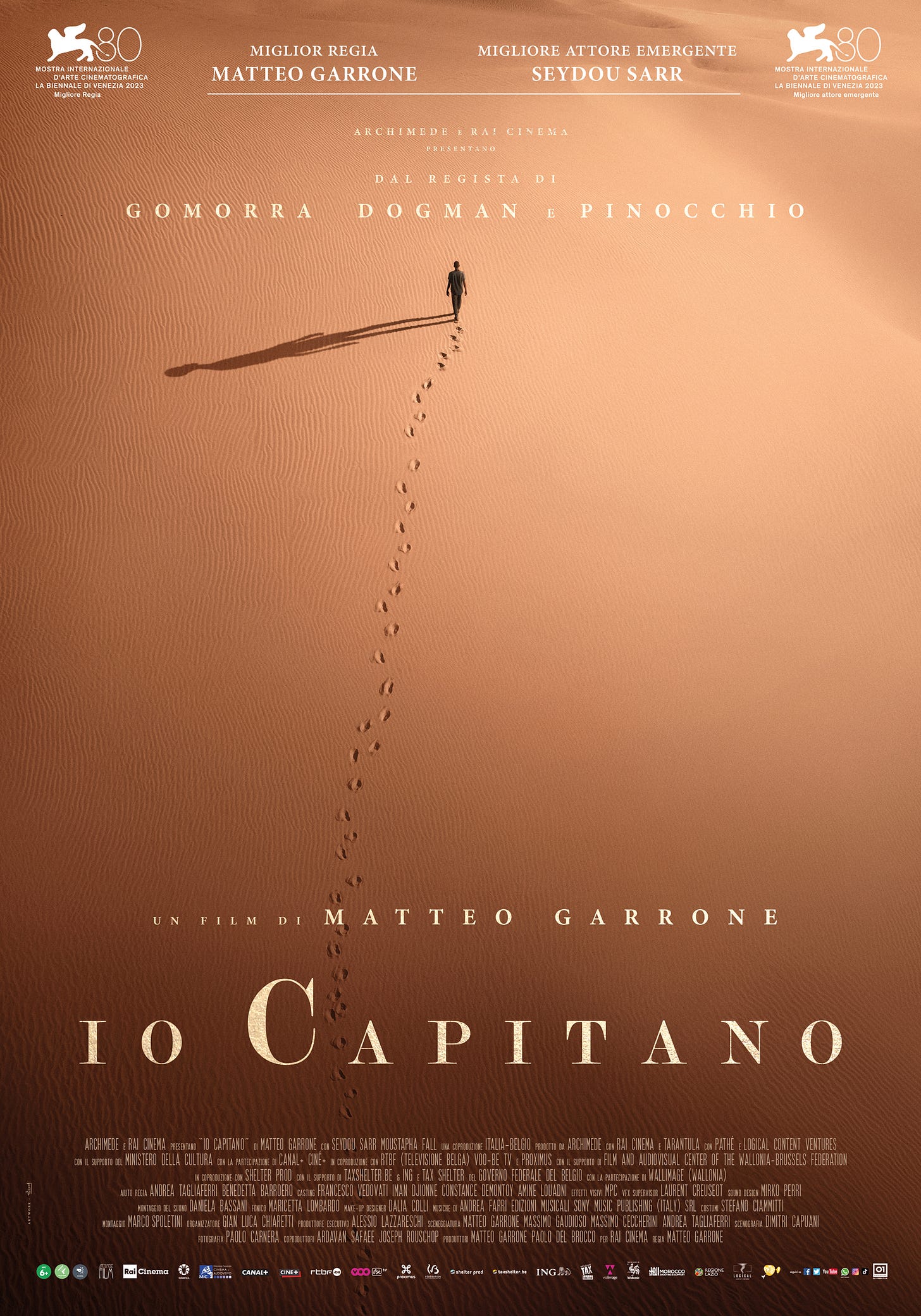

5 Questions #13: Gomorrah, Dogma, Pinnocchio, and now: Io Capitano, a director of boldly distinct and distinctly bold films

Do some filmmakers choose to set challenges for themselves that are far higher than others ever contemplate? A great story or great character or compelling situation is hard enough, but what about all the production challenges of heat, language, crowds, and authenticity? Picture yourself in a land not your own, or maybe on the water in a boat so full of people no one can move. And what if within this logistical nightmare, your film is really about the heart and soul of a young person, and the person you’ve found has never acted in a film before? Would you expect that actor to win a prize at Venice?

If someone pitched me Io Capitano, as much as I know I would like to see it, I would never believe it could be made, and yet here it is — and then some! And then when I place it next to director Matteo Garrone’s other work, I would not see the line that takes me from there to this. I really dig his movies and have seen a lot of them. I look forward to what he will always do next, and even more so now that I have had the remarkable experience that is his latest. Wow. A feat and a treat.

Every film has barriers and obstacles to getting made, but the production challenges of your latest film, must have out done them all. Desert, ocean, boats, crowds, tight spaces, children, night, heat, the list goes on. How did you do it? I just picture the crew and cast and you all totally worn out. Was there one particular challenge or string of challenges that were particularly challenging? How did you confront it? What did you learn from it?

We did a lot of research. We watched videos of torture, of dead people in the desert, there is plenty of material. The screenplay was written with several young people who had lived through the experience we witness in the film. Mamadou Kouassi, Fofana Amara were some of them. It was sort of like making a collage. I took the parts of several different real-life journeys and blended then together. It’s a mix of stories, all based on real life experience that we turned into a single long voyage.

Many of the extras and crew had made the journey themselves, and they were proud to show the team, and the world, what it feels like to make this kind of journey, because often they simply aren’t believed. They were open, generous, and trustworthy, and they were also the movie’s first audience because they were in front of the monitor with me during filming. We made this movie together, and I always wanted their reaction to what we were creating.

I wanted to give these people a voice and be faithful to the stories they told me. The movie ends with the Coast Guard’s arrival near the Italian shore. But for Fofana Amara, who was 15 when he ferried 250 people to safety, he was sent to jail for six months on trafficking charges. He wasn’t a trafficker – he was the victim of an unjust system.

A particular challenge was during a boat sequence; we had no time for rehearsals and we were at the end of our own journey, which is why we got such intense performances from the actors with Seydou helping to pull dying men from the engine room up to the main deck. The actors who were gasping for air were recreating something they had endured in real life. Sometimes I felt like I was, myself, the first spectator of the scene.

Your actors are excellent and feel so of the world. Each face, body, gesture... perfect. Yet I suspect you had to work with a lot of non-actors and put them through some very tough situations. When working with untrained performers in highly intense situations and under difficult circumstances, what do you do to prepare them, to help them get to the performance you are seeking?

I worked with many different casting directors in several countries: Italy, Morocco, Tunisia, France and Senegal. I focused on the casting in Senegal in my search for the main actors after initially scouting Senegalese teenagers in France and Italy, and growing frustrated because a young European immigrant’s point of view was so different from an African who had never left the continent. It was so important to me to find actors who hadn’t left their country of origin – who had never set foot in Europe. We ultimately found them in Dakar. Seydou lived in Thies, a little village 30 minutes far away Dakar, and Moustapha lived in Dakar.

Like many young people in Africa, Seydou and Moustapha dreamed of visiting Europe but had never left Senegal. They had the same restless desire to escape their country of origin as the characters we had written. This is the reason I didn’t give to them the screenplay. So they could live through the journey day by day. From the outset, they didn’t know whether their characters would succeed in their journey or not. The dreams of the lead characters were the same as our lead actors, a sort of marriage between fictional teens and the real people who played them. Every day during production, they had to succeed in a new adventure with the risk of the death for the characters if they didn’t survive.

While I found Seydou to be sweet and naïve when we cast him in Dakar, I never imagined he would go on to bring so much intensity to his presence on screen.

The chaos of filming in the desert heat grew into something unexpected, and touching. Seydou nailed the first two takes of the scene, but on the third take, the one you see in the movie, he started crying. Later that evening he told me his father had died in his arms in a similar way. When he was acting in the scene, he was seeing his father, not the woman.

Can you share a bit about how your path forward prepared you to make this film? What were some of the original sparks that got enflamed along the journey, and where did you accumulate the learnings that helped you overcome the obstacles that you would face in the making?

It took me a while to tackle this film after I heard a story that inspired me. I wanted to capture what we rarely see in immigration-themed movies, which is the journey of the migrants before they arrive at their destination. We are used to seeing the last part of the journey — the image of the boat arriving — followed by the ritual count of who’s alive or dead. Behind all the numbers and statistics are people with dreams, and families. We want to humanize this number.

I wanted to tell this story from the migrant’s point of view, like a reverse shot, revealing what we in Europe know, but never see. This is a first-person, life-or-death journey from Africa to Europe, an eternal journey for anyone who has sought out a better life. I always believed it was very important to keep the story simple and real. Above all, we had to be invisible. We tried to work in such a way that the spectator could immerse into the story and forget about all the rest.

On set I constantly verified the screenplay with young men who had gone through the experience of crossing the desert and being in the prison camps. They were always next to me. The people who had lived through the adventure were always behind the monitor, and I checked their reactions closely to make sure the story we were creating was in synch with them. My greatest fear from the start was to enter a culture that wasn’t my own; for me, I’d like to be an intermediary.

When I consider embarking on getting a film made, one of my first questions is “Why this film now?”. So: why this film now?

This is a movie about human rights, about people going to great lengths to travel to far away, unfamiliar places to find that better life. They see Europe as this free country where you can achieve anything. So this film is necessary to sensitize audiences about the right that all we have to move from their county to another without the risk of losing their life. In the last 15 years, 27,000 people died making this journey. We are used to thinking that migrants arriving in Europe by boat are fleeing desperate situations, but they are also making the journey to discover the world and follow their dreams. Young Africans have a window on European culture – they watch rappers and football on TikTok and Instagram, so they see our world and it looks full of life and full of promise, but they don’t see the reality behind all that. So I was pushed by this impetus to show the world their journey, their desire, their wishes. This is an epic odyssey, but also another perspective that shows the tragedy surrounding the immigration experience.

I made this film because, at a certain point, I realized that I felt a calling. I felt that there was a part of this voyage that was unknown in the Western imagination. We have to learn about it. To live the experience with them.

If we want to change the world, we can turn away from challenging subjects or approaches, but simultaneously it often means we will be making it hard to get placements or acquisition from leading platforms, not to mention the media attention that is needed to make an impact. How do you balance that.

We didn’t want to change anything, we wanted to give audiences the opportunity to live the experience of this journey – full of emotion and struggles – through Seydou’s eyes.

Every movie is the result of collaboration, because you are making something with a variety of different people, but this film was more collaborative than usual because I was shooting outside of my native language. I didn’t understand anything when I was directing the actors – many of whom were not trained actors themselves. I found myself directing to the sound of their language, and them. I think this is also the magic and the power that only cinema contains.

Io Capitano will be released theatrically in the United States on Feb. 23 via Cohen Media.

Matteo Garrone (Writer, Director, Producer) was born in Rome in 1968. In 1997 he made his first feature film, Terra di mezzo, with his production company, Archimede. In 1998 his second film, Guest (Ospiti) and in 2000 Roman Summer (Estate romana). The Embalmer (L’imbalsamatore), from 2002, received the David di Donatello award for Best Screenplay and Best Supporting Actor and the Nastro d’Argento (Silver Ribbon) for Best Editing. In 2005 he was in competition at the Berlinale with First Love (Primo Amore), and was awarded the Silver Bear for best soundtrack.

In 2008, Garrone wrote and directed Gomorrah, which won the Grand Prix at the Cannes Film Festival; he won five European Film Awards including Best Film and Best Director, seven David di Donatello awards and 2 Nastri d’Argento prizes; Gomorrah was selected by Italy as the entry for Best International Film (then known as Best Foreign Language Film) at the Academy Awards and entered the Golden Globes as well as receiving BAFTA and César nominations.

With Reality (2012) Garrone again won the Grand Prix at the Cannes Film Festival, followed by three David di Donatello awards and 3 Nastri d’Argento prizes; he returned to Cannes in 2015 with Tale of Tales (Il Racconto dei Racconti), winning 7 David di Donatello and 3 Nastri d’Argento awards.

In 2018 Dogman was awarded the Best Actor prize at Cannes, subsequently winning 9 David di Donatello and 8 Nastri D’Argento prizes before being selected by Italy as the entry for Best International Film (then known as Best Foreign Language Film) at the Academy Awards

In 2019 he brought Pinocchio to theaters, winning 5 David di Donatello and 4 Nastri d’Argento awards as well as earning two Oscar nominations for Best Makeup and Best Costume Design.

Please read this editorial from the NY Times: https://www.nytimes.com/2024/03/04/opinion/oscars-italy-io-capitano.html

What an important and powerful piece this is.

I truly loved this film.